Robert Falcon Scott arrived at Cape Evans on January 5, 1911 and within two weeks erected and occupied the “Terra Nova” Hut–named after his ship. It was the largest and best built hut in Antarctica and housed up to 25 people and 17 ponies. Scott’s plans were both scientific and exploratory, notably a push for the South Pole. After being nearly beaten in this goal by Ernest Shackleton three years earlier and then learning of Amundsen’s southern ambitions, Scott redirected all his energies into reaching the South Pole. His expedition style couldn’t have been more different than that of Amundsen’s. He carried with him three Wolesley Motor Sledges–poorly designed and tested. One never reached the shore when it crashed through the ice and sank. The two others were abandoned at “Corner Camp” less than 100 miles from Cape Evans. By contrast, Amundsen’s party consisted of only five men and nearly 100 dogs and within 99 days had conquered the Pole and returned in comparative comfort.

Scott’s South Pole party consisted of 16 men, the two remaining Wolesley Motor Sledges, 8 horses and about 25 dogs–all staged to leave camp at different times as to arrive together at their evening camp. Scott was not a planner. He had never skied in his life until forced to do so after the sledges broke down. He had a mistrust for dogs (and most of his men, for that matter) and regarded “man-hauling” his sledges as the noble way to travel. After reading Shackleton’s preference for white horses, Scott insisted on the same–limiting himself to 50% of the available stock. They all died of starvation and intense cold before they left the Ross Ice Shelf. His men were underfed and dipped into the returning caches on the approach. The caches were poorly marked with one cairn and were easy to miss. Amazingly, he allowed only 4 days of bad weather for the entire polar trek. Naturally, his party slowly starved on 2/3 the caloric intake that was considered a minimum for the trek to the pole by Sir Edmund Hillary in 1957–and this was motorized. Some say that Scott’s final error was including a fifth member in his party for the final push to the Pole which further strained their tentage and rations. Incredibly, the original four had no surveying experience. Indeed, they made the Pole only to find Amundsen’s tent left there 35 days before. Thoroughly depressed, the march back to Cape Evans deteriorated into a slow death-march: Evans dying of scurvy and exhaustion, then Oates walking into the blizzard and the final three (Scott, Wilson and Bowers) succumbing in a frozen tent only 11 miles from “one ton cache.”

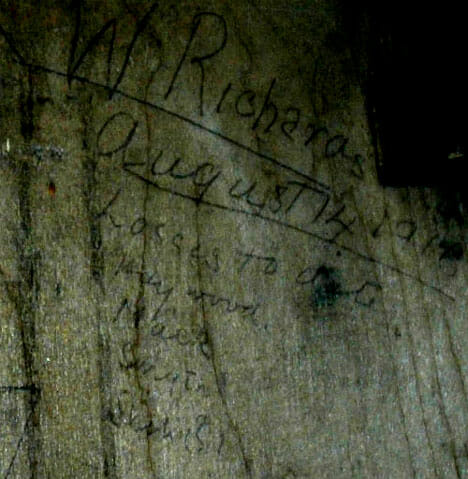

It is hard to imagine the expedition hardships that were self inflicted by blind obedience and poor leadership. Seven out of eight horses were lost in the earlier depot-laying party when Scott ordered a direct path to be taken back to Hut Point. Prior to leaving for the Pole, Wilson, Bowers and Cherry-Girrard man-hauled sledges to Cape Crozier, on the other side of Ross Island, in mid winter to gather penguin eggs. Temperatures were consistantly at minus 60F; their entire camp blew away in a blizzard yet they stumbled around in darkness for a month before returning to Cape Evans with only three eggs. (see Apsley Cherry-Gerrard’s “The Worst Journey in the World”) The Cape Evans Hut was also used by Shackleton’s Trans-Antarctic Expedition (1914-1917) as a base to lay depots across the Ross Ice Shelf. Unfortunately, their ship, Aurora, blew out to sea and was lost with most of the provisions. Nevertheless, the men manufactured wooden shoes out of box crates and raided the three existing huts for enough provisions to complete their tasks loosing three men in the process. A most telling epitaph is that of Dick Richards’ of the 1915-1917 Ross Sea Party. On the inside of his bunk was penciled “RW Richards August 14, 1916–Losses to Date” then four names: “Haywood, Mack, Smith and Shack (?)” for Ernest Shackleton had by then been stranded in the ice 3000 miles across the continent and was presumed dead. Of course, Shackleton survived his ordeal after losing his ship Discovery to the ice and returned in 1917 to rescue his men. This marked the close of the heroic-era.

Today, the hut survives almost exactly as it was when Scott and his men occupied it. A penguin about to be skinned (the men sold pelts to finance the expeditions) lies frozen on the table next to a copy of the London News (February 29, 1908) . This is not a museum but a moment frozen in time. How to preserve these sites is a complex issue with the Antarctic Heritage Trust with Shackleton’s hut 5 miles north listed as one of the 100 most endangered sites on Earth. Next week we’ll show you some of the life around town–and maybe a penguin or two. Stay tuned…..